Reading the Abu Ramadan trilogy alongside the constitution

Article Index

The Abu Ramadan Case went before the Supreme Court for the third time last Thursday, 23rd June, 2016. In its latest pronouncement on the matter (“Abu Ramadan III”), the Court has ordered the Electoral Commission to “clearly set out in writing, the steps and modalities that the Commission intends to take in order to ensure full compliance with the Court’s order” made on 5th May, 2016.

Advertisement

That earlier order, as the Court recalled, commanded the Commission to “take steps immediately to delete or ‘clean’ the current register of voters to comply with the provisions of the 1992 Constitution and applicable laws of Ghana” and “also afford such affected persons the opportunity to re-register.” The Commission is also ordered to submit in writing to the Court the full list of all the persons on the register of voters who were registered as voters by the Commission on the basis of their possession of a National Health Insurance identification card. The Commission is to comply with these latest orders by 29th June, 2016.

Abu Ramadan III apparently became necessary as a result of the public confusion and misunderstanding, divided largely along party lines, caused by the vastly contradictory readings and interpretations proffered by various legal and opinion commentators to the judgment and orders of the Supreme Court delivered on 5th May, 2016 (“Abu Ramadan II”).

The ensuing confusion caused one of the Justices who had sat on the case to take the unusual step of offering, in an extrajudicial context, a clarification of the judgment in response to a question from the press, a move that generated collateral controversy of its own. Even the Electoral Commission, the primary defendant in the case and the party to which the Court’s orders were directed, was reportedly unable to determine what, if anything, the judgment and orders of the Court in Abu Ramadan II required of it.

The Abu Ramadan trilogy began with the decision of the Supreme Court delivered on 30th July 2014 in two consolidated suits, J/11/2014 and J/9/2014, brought by Plaintiffs Abu Ramadan and Evans Nimako and by Plaintiff Kwasi Danso Acheampong, respectively (“Abu Ramadan I”). The plaintiffs in Abu Ramadan I had sought, among others, “a declaration that upon a true and proper interpretation of Article 42 of the Constitution of the Republic of Ghana, 1992 (hereinafter, the ‘Constitution’) the use of the National Health Insurance Card (hereinafter, the Health ID card) as proof of qualification to register as a voter pursuant to the Public Elections (Registration of Voters) Regulation 2012 (Constitutional Instrument 72) is unconstitutional, void and of no effect.” The Plaintiffs’ case was based on the fact that while article 42 of the Constitution restricts the right to vote and to be registered as a voter to a “citizen of Ghana”, the National Health Insurance (“NHI”) card is available and may be issued to any resident of Ghana, without regard to nationality.

In a unanimous decision, the Supreme Court granted the relief sought by the plaintiffs in Abu Ramadan I, declaring that “the use of the NHI card to register a voter pursuant to Regulation 1(3)(d) of the Public Election (Registration of Voters) Regulations, 2012 (C.I. 72) is inconsistent with the said article 42.” The Court further granted an order of perpetual injunction restraining the Electoral Commission from using the National Health Insurance Card for the purpose of registering a voter under article 42 of the Constitution.

It appears that the Electoral Commission, while ceasing to accept NHI cards for future voter registration following the decision in Abu Ramadan I, did not read Abu Ramadan I as requiring it to remove or exclude from the current register of voters those persons who had previously been registered on the basis of a NHI card. The Plaintiffs, therefore, returned to the Supreme Court two years after Abu Ramadan I had been delivered, contending, among other things, that “following the declaration of the unconstitutionality of the use of said cards, names of persons who used it in the registration process conducted under CI 72 cannot continue to remain on the register of voters.” It is in response to this claim that the Supreme Court in Abu Ramadan II ordered the Electoral Commission to delete from the current register of voters the names of those persons who were registered as voters on the basis of a NHI card and offer the affected persons a fresh opportunity to register using a constitutionally-compliant form of identification.

Rather than end matters, Abu Ramadan II generated a new storm of controversy as to the meaning and implications of the Court’s judgement and accompanying orders. Indeed, despite Abu Ramadan III, it appears that the debate sparked by Abu Ramadan II is far from over. The issues at stake in the Abu Ramadan trilogy, but especially in Abu Ramadan II, are far from academic; they are weighty and urgent. The Court’s judgment in Abu Ramadan II touches on very important and fundamental constitutional questions, notably the Supremacy of the Constitution, the role of the Supreme Court in enforcing fidelity to the Constitution, and what the independence of the Electoral Commission means within our constitutional system.

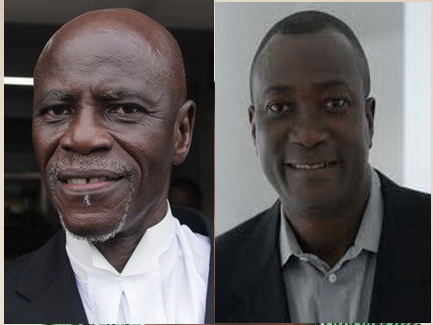

Moreover, the specific questions presented to and answered by the Court in the Abu Ramadan trilogy bear directly on the content and integrity of the voters register that is to be used in this year’s presidential and parliamentary elections--which elections are only a few short months away. In light of this, and because certain propositions contained in the Abu Ramadan II judgement written for a unanimous court by Justice Gbadegbe, remain deeply troubling and were not taken up again in Abu Ramadan III, we have decided to enter this debate, primarily to return to Abu Ramadan II and subject to close scrutiny the controversial propositions in that case as well as the meaning placed on those words and the orders of the Court by certain legal commentators.

For the purposes of this article, we have divided into two parts our analysis of Justice Gbadegbe’s judgment for the Court in Abu Ramadan II. The first part deals with certain general propositions and questions of constitutional law that are contained in the “discussion” portions of the judgement and whose meaning and implications are far-reaching and extend beyond the specific issues presented in the case.

There are two main issues here: (a) the effect of a declaration by the Court that a certain law or provision of a law is unconstitutional; and (b) the meaning of the Independence of the Electoral Commission as it relates to the power of the Supreme Court to enforce the Constitution. The second part deals with the specific orders of the Court; specifically, what action, if any, is required of the Electoral Commission under Abu Ramadan II in order to bring the voters register in compliance with the applicable provisions of the Constitution, as interpreted by the Court. We shall deal with these issues one after the other.

I.(A) Is an Unconstitutional Law Void or Not?

The first broad or general question of constitutional law that arises from the judgement in Abu Ramadan II may be framed as follows: What is the effect of a Supreme Court declaration that a law or provision of a law is unconstitutional? More specifically, can a law or an act continue to have validity as law despite a determination and declaration by the Supreme Court that the law or act in question is inconsistent with the Constitution?

Language in the judgment of the Court in Abu Ramadan II appears to suggest that this last question can be answered in the affirmative. That language is the genesis of some of the confusion that this case has generated. The relevant portion of the judgment written by Justice Gbadegbe reads as follows: “As the registrations were made under a law that was then in force, they were made in good faith and the subsequent declaration of the unconstitutionality of the use of the [NHI] cards should not automatically render them void.”

In essence, the Abu Ramadan II Court wishes to say that, an act that has been found and declared by the Court to be unconstitutional may nonetheless retain current and prospective legal validity. The theory or reason the Court gives for this proposition is that, at the time the act was done the law under which it was done was a valid law as it had not yet been declared to be unconstitutional.

This is a profoundly extraordinary and deeply troubling proposition as a matter of constitutional jurisprudence. Since every act, until it is found and declared to be unconstitutional, can be said to have been done in good faith compliance with existing law, the upshot and implication of the Court’s statement, even if unintended, is to allow an unconstitutional law or act to continue to be applied despite having been found and authoritatively declared to be unconstitutional.

Unfortunately but understandably, no authority or citation either to a provision of the Constitution or an established constitutional precedent is provided by the Court in support of this novel proposition. The absence of supporting authority or citation is not surprising, because one will have to search but in vain in our constitutional jurisprudence, and in the jurisprudence of every other constitutional system analogous to ours, for an authoritative support for the proposition that a law declared by the apex court to be unconstitutional is not void and thus can continue to be enforced or applied.

It would be easy to disregard the above proposition as mere dictum were it not for the fact that these words come from a unanimous seven-member panel of the Supreme Court and touch on arguably the most important and fundamental question in our constitutional system, namely the meaning of the Supremacy of the Constitution. So fundamental is the doctrine of the Supremacy of the Constitution, and of the related question of the effect of a judicial declaration of unconstitutionality, that the Framers of the Constitution gave it pride of place as the very first article of the 1992 Constitution. And it is to that provision that one must have recourse in seeking an authoritative and clear resolution of this matter.

Article 1, clause 2, of the Constitution states: “This Constitution shall be the supreme law of Ghana and any other law found to be inconsistent with any provision of this Constitution shall, to the extent of the inconsistency, be void.” Article 2 of the Constitution then proceeds to lodge exclusively in the Supreme Court the power to determine and declare authoritatively whether a challenged law is unconstitutional.

The combined effect of these two preeminent provisions of the Constitution is clear and straightforward: If the Constitution is the supreme law of Ghana; and if it lies within the exclusive province of the Supreme Court to declare that a law is unconstitutional; then, a law declared to be unconstitutional by the Supreme Court, is definitively void and, therefore, of no legal effect. To say otherwise, that is to say, to suggest that a law found and declared by the Supreme Court to be unconstitutional is nonetheless not void and, thus, retains continuing validity for any reason whatsoever is to negate the notion of the Constitution being the supreme law of Ghana.

It is, of course, possible to find jurisdictions or constitutional systems in which a law declared as unconstitutional by a final court is still not automatically void. But what distinguishes those jurisdictions, such as the Netherlands and Switzerland, from ours is that, in those constitutional systems, the Court does not have the final authority to decide the fate of a law it has found to be unconstitutional. In those systems, it is usually the Legislature or Parliament that retains the final say as to what to do about a law declared by a court to be unconstitutional.

The Legislature may choose, in those jurisdictions, to retain the law despite the judicial declaration of unconstitutionality. In other words, those jurisdictions follow the doctrine of parliamentary supremacy. That, however, is not the kind of constitutional system in force in Ghana. Under Ghana’s constitutional system, dating, at least, as far back as the 1969 Constitution, it is for the Supreme Court to declare a law unconstitutional and, the 1992 Constitution, like its predecessor constitutions, is emphatic that, once such a declaration has been made by the Court, the affected law is automatically void.

The view has been propounded in some quarters that an unconstitutional law may be voidable, but not necessarily void. This is a rather fanciful proposition. The concept of voidability is a concept known to contract law but completely unknown to constitutional law. In contract law, where the parties are deemed autonomous and self-interested and, therefore, best suited to protect their own interest, a party may, under certain circumstances, choose to be bound by a contract although the contract may contain a legal defect that would otherwise render it void and give the party the right to walk away from the contract. In those circumstances, contract law doctrine leaves it to the affected party to decide for himself or herself whether to proceed with the contract or not.

It is obvious why such a doctrine or concept has absolutely no place in constitutional law—certainly not under the constitutional system and jurisprudence that operates in Ghana and in every other known common law jurisdiction. Not every concept recognized in one branch of the law may be transferred or imported into other branches of the law. The concept of a voidable contract is one such concept that is limited in its application to the realm of contract law. At any rate, Article 1 of the Constitution speaks only of an unconstitutional law being void, not voidable. And it is for good reason that the term voidable is not the term used in the Constitution—the contract law concept of voidability simply does not make sense in the constitutional context, definitely not in a constitutional system where the Constitution is the supreme law of the land.

The question remains as to when or at what point in time a law is deemed to be void once it has been declared unconstitutional. There are two possibilities. The first view, which is the settled view under Ghanaian constitutional jurisprudence, is that when a law is void for unconstitutionality it is “void ab initio”—that is to say, it is deemed to be void from the moment of its enactment, even before it is formally declared unconstitutional. The second possibility is that, a law declared unconstitutional, though void, is void only from the moment it is declared unconstitutional. There is no third way. Thus, whether one applies the first or the second position, which is to say, whether an unconstitutional law is void ab initio or void with effect from the time it is declared unconstitutional, once it has been declared unconstitutional, it ceases, at the minimum, to have legal validity immediately and prospectively.

The proposition put forth by the Court in Abu Ramadan II, however, appears not to embrace either of these two possibilities. Instead, the Court appears to suggest that a law that has been found and declared unconstitutional may nonetheless continue, in some way, to have current and prospective validity—in other words, that such a law may still not be void. That position is clearly erroneous and completely at odds with the doctrine of the Supremacy of the Constitution enshrined in Article 1 of the Constitution. If the Constitution is the supreme law of the land and the Supreme Court has the final authority to declare a law unconstitutional, then no law that has been so declared by the Court can co-exist with or under the Constitution. This much is trite law.

The Supreme Court in Abu Ramadan II appears to have been led to its untenable proposition by a concern that to rule that the NHI card, having been declared unconstitutional, ceases to be useable immediately (currently) would amount to a retroactive application of the declaration of unconstitutionality. This is bizarre reasoning. In fact, whenever a court holds that an unconstitutional law is void ab initio, it is essentially applying the ruling of unconstitutionality back to the time the law was enacted. To say that, this amounts to a “retroactive” application of its ruling and is thus improper amounts to saying, in effect, that the very idea of an unconstitutional law being void ab initio is problematic.

But since when did this well-worn doctrine of void ab initio, which is deeply embedded in our constitutional jurisprudence, become problematic? To the contrary, to throw the doctrine of void ab initio into doubt, as the Court’s language does, creates real absurdity. Are we going to continue to hold a person in prison after finding and declaring unconstitutional the law under which he was charged, prosecuted and convicted, on the theory that to apply the unconstitutional ruling “retroactively”—which is to say to hold that the law is void ab initio--is untenable because that person’s conviction was done in good faith under a law that had not been declared unconstitutional at the time?

The Court also appears to have been concerned that, saying that the unconstitutional law is void ab initio might raise doubts about the legality or constitutionality of past elections conducted and concluded on the basis of a voter register containing NHI registered voters or that it might cause manifest injustice to the affected voters. But this concern, too, is totally unfounded. The doctrine of void ab initio has never been applied and is never applied to undo acts that have already been legally and practically concluded and which, therefore, no longer present a live legal controversy.

Thus, for example, there is no danger to the validity of any past election in which NHI cards were used by holding now that the use of NHI cards is unconstitutional and, therefore, void. Elections that have been held and conclusively decided and settled, and pursuant to which a government has been lawfully and irreversibly installed, cannot legally or practically be undone by a subsequent finding or declaration that certain voters who may have voted in those elections were registered as voters using an unconstitutional form of identification. That matter simply does not arise after the fact.

The notion that applying the void ab initio doctrine in these circumstances might cause a “nuclear meltdown” (to borrow a phrase from another one of the Court’s past decisions infected with the same fallacy) is simply a red herring. For example, when the Supreme Court ruled that prisoners were entitled under the Constitution to be registered as voters and, thus, proceeded to declare as unconstitutional and void the existing law that denied prisoners the right to be registered to vote, no one could be heard to argue that such a declaration would call into question past elections that had wrongfully excluded prisoners from voting.

That point was legally moot. Prisoners would be duly entitled to be registered in voter registrations that were conducted after the ruling. Similarly, any question or doubt as to the validity of past elections arising out of a subsequent declaration that use of the NHI card is unconstitutional is simply moot as a matter of law. Indeed that question was never before the Court in the Abu Ramadan Case, because it simply would have had no legal legs to stand on. The Court’s jurisdiction is properly reserved for deciding live and present legal controversies; not moot or dead issues.

In any case, the Constitution is clear as to the timeframe or window within which presidential or parliamentary elections may be challenged in court, and that window had long closed irreversibly as of the time of Abu Ramadan I. The impact on past elections of applying the void ab initio doctrine is, therefore, not a concern that should have detained the Court’s attention for even one moment.

At any rate, if the Court felt any unease, for whatever reason, in saying that the use of NHI cards was void ab initio, it could simply have resorted to the alternative doctrine of voidness by saying that the unconstitutionality ruling applied only to the contents of the voters’ register as from the time of the decision, including those that would be compiled and used (and thus to elections that would be held) after the declaration of unconstitutionality.

In other words, the unfounded fear or concern that seems to have detained the Court’s attention needlessly in Abu Ramadan II, causing it to make the untenable proposition it made, is easily and correctly addressed by saying that the declaration of the NHI card’s unconstitutionality would take effect from the date of the declaration of unconstitutionality.

In fact, that, in essence, is what the Court did when it offered those who had been previously registered using the NHI card the equitable remedy of a fresh opportunity to get registered currently using a constitutionally-compliant form of identification. Having offered all affected NHI-card registrants that just and sufficient remedial opportunity, there was no longer any manifest injustice that might be visited on such persons for the Court to be concerned with. There was, therefore, absolutely no need for the Court to turn the Constitution and well-established constitutional doctrine on its head by suggesting that an unconstitutional law is not necessarily or automatically void.

Instructively, the question as to whether a declaration of unconstitutionality made the unconstitutional act automatically void or not did not arise in Abu Ramadan I. Perhaps the Court there assumed, reasonably, that the answer was obvious or else was clearly implied from its judgement written (again for a unanimous panel) by the Chief Justice. After all, Plaintiffs in Abu Ramadan I had prayed the Court specifically for a declaration that, having regard to article 42 of the Constitution, use of the NHI card as proof of qualification to register under CI 72 “is unconstitutional, void, and of no effect.”

Having granted that relief by declaring the use of the NHI card for voter registration purposes as unconstitutional, the Court arguably deemed it obvious (and thus unnecessary for it to repeat the point) that, the use of the card for voter registration purposes became instantly and prospectively void. In fact, the judgment of the Chief Justice in Abu Ramadan I begins with a citation to Article 1(2) and a statement by the Court that, by virtue of “the doctrine of constitutional supremacy” embodied in article 2(1) (as well as article 130(1)), it is the Court’s duty “to determine the constitutionality of legislation and to declare as void any law which is found to be inconsistent or in conflict with any of its provisions.”

In light of these constitutionally incontestable statements in Abu Ramadan I, it is hard to understand why the Court in Abu Ramadan II strayed into uncharted waters with its needless and insupportable suggestion that an unconstitutional law or act may not be automatically void. Having rightfully devised an appropriate equitable remedy for those voters affected by the unconstitutionality ruling, there was no further need or warrant for the Court to, in effect, jettison Article 1 of the Constitution and thereby shake the very foundation of the Constitution by disturbing the fundamental doctrine of the Supremacy of the Constitution.

The damage to the doctrine of the Supremacy of the Constitution as well as to the Court’s own authority under Article 2 and to the integrity of Ghanaian constitutional law and jurisprudence that would arise from the Court’s erroneous pronouncement to the effect that an unconstitutional law is not automatically void is so grave and untenable that that proposition cannot be allowed to stand.