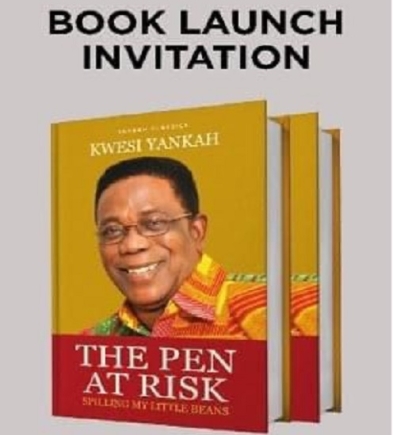

Book Review: The Pen At Risk

Warning: If you are recently bereaved, this book is not for you: loud guffaws or pantomimic laughter will be unavoidable and folks might wonder what’s wrong with your head.

Advertisement

But The Pen At Risk is also a roller coaster experience: pages after pages of steep emotional inclines and descents contrasted with sudden ascents.

It is a thrill ride in which emotions peak in the celebration of heroes and drop at the unmasking of a tyrant here, a hypocrite there, in government and in academia.

This is quintessential Kwesi Yankah (the Kwatriot himself, alias Abonsam Fireman), a word aficionado, Ghana’s only surviving written word linguist gifted with words and the art of crafty story telling.

Kwesi Yankah is telling the story of his life’s journey, most of it in academia.

It is a journey whose “ripples also took me through a whirlwind of national politics, which I survived limping”.

Tales well told.

But, is The Pen At Risk a faithful hypothesis linking the rumours and gossip to the real dangers in which writers and broadcasters found themselves in the various totalitarian regimes of Ghana?

For the purpose of this review, a pen is a pen, wielded either in academia or by the media.

Evidence that his pen was at risk was when WAEC invited him to give the 21st public lecture in its Endowment Fund lecture series.

For a topic, Yankah chose to speak on Ghana’s vacillating senior high school policy.

Three days before the event, WAEC wrote informing him that the lecture had been put on hold.

Then he discovered that notices had gone out announcing a substitute speaker for the day, who was to speak on a different topic.

WAEC was later to confess that Kwesi’s lecture was postponed because it had the potential of “generating political controversy, especially in an election year”.

His pen was at risk when it came to his progression from senior lecturer to associate professor at the University of Ghana.

A faculty review committee chaired by the Dean of the Faculty turned down the application.

Yankah ran amok: “Through laid down channels, I got access to assessors’ reviews from the Dean’s office, and found a damning review by one assessor which tipped the scales against my application... Reality checks betrayed dishonesty in the assessment.”

Drama

Talking of university politics, drama was to follow.

The Dean’s first term was drawing to a close and had applied, seeking a second term, which was often automatically granted by popular vote.

Yankah went to work.

How he, with the help of a number of the faculty members, put up an alternative candidate, how the Dean’s supporters nearly succeeded in dissuading this alternative candidate and how the final result showed that the Dean lost by a lone vote, is the stuff by which high noon drama was made.

There is more where this one came from — call it “spiritual academia”.

From 1977 honours upon honours were piling on Kwesi Yankah.

Now professor of Linguistics, he had been appointed Dean of the Faculty of Arts and also Hall Master of Sarbah.

“The weekend before I started work as hall master, I received a handwritten note from a worker, who volunteered a word of caution and advised that I should ‘Bring your own executive swivel chair’.”

That was done.

As early as 8. 15 am on D-Day the alleged suspect opened the door.

He had come to pay a courtesy call and welcome the new Hall Master.

There were other pens at risk, including one wielded by Prof. P.A.V. Ansah.

In the 1970s, he, as the Editor of Legon Observer, was picked up at midnight for an article he had written denouncing military brutalities on innocent civilians.

Now, in the 1980s, his wife, speaking to Yankah, reports that “a friend of his came home to show him a hit list in which his (Ansah’s) name featured.”

Then came the era of “shit-bombing” ̶ spraying faecal matter in the offices of the critical media.

Next was the pen of Kwaku Sakyi Addo.

In 1998, his GTV programme, ‘Kweku One on One’, was a must-watch.

The first four episodes featured political and social celebrities.

Next to be featured was a prominent politician from the opposition.

Yankah recalls that “the highly informative TV show was dramatically taken off the screen with virtually no explanation, compelling its host to write a letter of protest, published in the media.”

Radio Univers, the radio station belonging to and located at the University of Ghana was next on the hit list. Yankah recalls that “One morning, officials from the National Communications Authority came and ordered us to stop operations, since we were violating the laid down terms for experimental broadcasting, which also prohibited us from broadcasting beyond 9 pm.”

Guess who led students in a fearless defence of democracy: “The Vandals from Commonwealth Hall led the crusade and took turns to collectively keep vigil around the radio station over a week, until the footsteps of NCA receded in the distance”.

Proven

Thus far, the thesis of Yankah’s Pen At Risk can be deemed as successfully proven or defended.

But that is a little over 50 per cent of the score.

The other 50 per cent is the process by which the writer became a famed public intellectual and respected academic, impacting the world with his mind.

From his days as a doctoral student, Yankah’s agenda has been “to explore areas of spoken language and communication that overlap with cultural practice”.

In this exploration, he fought stereotypes against Africa, and won.

As he points out, “many academic breakthroughs in the humanities would have emerged from the continent, but for the skewed politics of knowledge production which trivialises non-western knowledge...puts scholarship from Africa in perpetual bondage and dislocates scholarly authority on Africa”.

Yankah is not done.

He takes on Ghana’s university accreditation system.

Questioning the use of the very nomenclature, “university college”, he finds it ridiculous that “in 2014, the Central University College was still an affiliate institution, while University of Health and Allied Sciences, and University Mines and Technology, which were new born babies, were receiving plaudits as fully fledged public universities.”

On Nkrumah’s overthrow in 1966, the Ghana Academy of Arts and Sciences, “in an unprecedented move, dismissed Nkrumah (the founder) from the organisation, “due to the embarrassment he had brought to the Academy as a tyrant, but also for the atrocities his regime had meted out to J. B. Danquah (a fellow), leading to his death.”

Curious

The Pen At Risk has no shortage of the curious and the bizarre.

Dear reader, get ready to be shocked beyond belief.

As recently as the last decade of the 20th century, there were (perhaps still are) people in Europe and North America who still think of Africa in Stone Age terms.

The author tells of an encounter in the United States with a lady from the Caribbean who insinuated to him that “it would take a little while for my (Kwesi’s) two little daughters to get used to wearing shoes!”

And now, what I call the mother of all shocks.

Kwesi mentions an experience in the home of a Ghanaian immigrant in America.

“Anytime the kids misbehaved, only one threat would bring them to instant order.

Father would yell, ‘Charles, if you misbehave, or do that again, I will take you to Africa; I say I will take you to Africa if you do that again.’

Any child hearing that knew the serious implications, and instantly restored good behaviour!”

The ‘Pen At Risk’ book is near perfection.

The things that take away from perfection include the excess liberties the author takes with commas.

At many places, they disrupt the smooth flow of otherwise excellent text.

Are you a student of the University of Ghana, or a former student?

Do you know the meaning of “naro”, as practiced among roommates?

Check from the pages of ‘Pen at Risk’.

This indeed, is a Yankah classic.

There are few like this book.