Ghana’s public debt crisis:Lessons for the future (3)

This is the third part of this article published last Saturday. Large financing needs and tightening financing conditions exacerbated debt sustainability concerns, shutting-off Ghana from the international market.

Advertisement

Large capital outflows combined with monetary policy tightening in advanced economies put significant pressure on the exchange rate, together with monetary financing of the budget deficit, resulting in high inflation.

These developments interrupted the post COVID-19 recovery of the economy as GDP growth declined from 5.1 per cent in 2021 to 3.1 per cent in 2022 to 1.7 per cent in 2023. World Bank (2022) find that the fiscal deficit widened slightly to 15.2 per cent of GDP in 2020 but further improved to 12.1 per cent of GDP in 2022 due to less spending. Public debt declined from 79.6 per cent in 2021 to over 88.1per cent of GDP in 2022, as debt service-to-revenue reached 117.6 per cent.

The country’s debt overhang sets in when the face value of debt reaches 60 percent of GDP or 200 percent of exports, or when the present value of debt reaches 40 percent of GDP or 140 percent of exports.

The monetisation of fiscal deficits, and Bank of Ghana lending to government through ways and means advances has risen to GHS 50billion in 2022, exceeding the threshold set by Bank of Ghana Act 2002 Act 612 as amended Act 2016 Act 918 Section (2) the total loans, advances, purchases of treasury bills shall not at any time exceeds 5 per cent of the total revenue of the previous fiscal year.

These ways and means advances are temporary overdraft facilities provided to Government of Ghana (GoG) to help with financial difficulties caused by a cash flow mismatch by bridging the gap between expenditure and revenue receipts.

This level of borrowing from the Bank of Ghana to finance fiscal deficit was clearly unsustainable, fueled inflation and endangering growth.

In Ghana, deficit financing has led to borrowings from the multinational finance institutions, such as the International Monetary Fund (IMF), the World Bank, African Development Bank (ADB) and Euro-markets amongst others.

Unfortunately, the rising national debt in Ghana begun to outweigh the country’s revenue generation capacity and drawing down on foreign reserves, hence stifling the much-needed public capital investments and economic productivity.

Also, it has been reported that these borrowed funds are often mismanaged and misapplied, hence, were not used for economically productive activities, leading to debt burden, capital flight and economic instability in the long run.

Ghana has accumulated huge debt with rising cost of debt service which has undermined economic stability as domestic investments are being crowded out by rising cost of debt servicing.

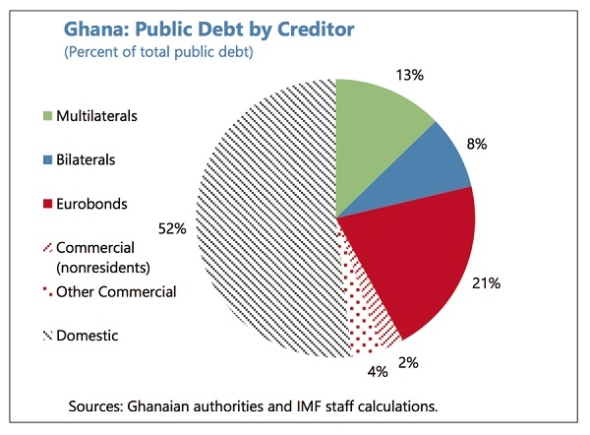

High debt levels resulted in high debt servicing, which has led to low the amount of money available for investment in infrastructure and other economic sectors. The Ghana’s debt profile continued to increase in the face of expanding fiscal deficit and low revenue generating capacity. This was concerning because the country’s debt profile became more and more dominated by commercial debt. Weak fiscal and economic performance over extended periods of time led to an unsustainable fiscal situation for Ghana in 2022 which led to the domestic debt restructuring.

One of the core issues in this contemporary Ghana trajectory has been rising public debt over four years.

When the crisis officially started in 2022 with a debt-to-GDP ratio around 88.1 per cent, it was interpreted by most economists and policymakers as a public debt crisis. As a result, the austerity measures of the last three years including higher taxes have been imposed in order to address this problem.

Fiscal consolidation, together with structural reforms, is supposed to generate large fiscal surpluses, reinvigorate investment, and enhance the competitiveness of the economy and thus net exports.

The result of these efforts will be a slowdown of the increase in debt and a boost to growth and therefore a decrease in the debt-to-GDP ratio. Austerity and structural reforms are thus imposed to a large extent in the name of the sustainability of debt.

The goal of the present paper is to provide a comprehensive and well-rounded examination of the issue of the Ghana public debt and its role in the crisis.

We start with a historical discussion of the accumulation of the Ghana public debt before 2016 and the reasons that led to the increase in the debt-to-GDP ratio over time.

A historical account of the Ghana public debt serves as a basis for the discussion of the role of the debt during the crisis. We make three main points.

First, the imposition of austerity and “structural reforms” in the name of debt sustainability has pushed the economy into a debt-deflation trap: austerity leads to a fall in the GDP and thus an increase – ceteris paribus – of the fiscal deficit.

These two effects lead to an increase in the debt-to-GDP ratio and make more austerity and more “structural reforms” necessary.

The swirling of the Ghana economy in this vicious cycle has grave social and political consequences.

This discussion of the experience of the last three years shows that Ghana’s public debt is clearly unsustainable; therefore, we argue that a bold restructuring of the debt is needed for the Ghana economy to reignite its engine of growth.

Ghana’s debt sustainability will depend upon four ingredients- primary balances; real growth devoid of higher inflation; real interest rates as well as reasonable debt levels.

Higher primary balances-the excess of government revenue and expenditure excluding interest payments and growth help to achieve debt sustainability, but unfortunately higher interest payments and higher debt levels are making debt sustainability more making challenging. An insistence on the current policies is not justifiable on pragmatic, moral, or any other grounds.