Dishonest naturopathy practitioners: Call for standardisation

Naturopathy or naturopathic medicine is defined by two core philosophies and seven principles and naturopathic practice that are guided by 12 distinct naturopathic theories.

According to the World Naturopathic Federation (2021), direct risks associated with naturopathic care have been reported very infrequently and the vast majority are minor.

Advertisement

Panesar et al., (2016) and Nabhan et al., (2012) are of the view that the main types of risks associated with naturopathic practice are similar to those from any other health profession, which employs a broad scope of practice and results primarily from tools of trade and the primary-care context within which they work.

Ghana is currently being recognised as a key player in the global Naturopathic community, by the World Naturopathic Federation (WNF) in their latest book on Naturopathy.

Minimum qualification

There can be no standardisation policy without education. The WHO recommends a minimum of 1,500 hours for Naturopaths and maximum of 4,500 for Naturopathic Doctors’ education.

This requirement is used by accredited Naturopathic Medical Schools globally and supported by the World Naturopathic Federation (WNF), Canada.

The full breadth of naturopathic knowledge covered in naturopathic educational programmes as recommended by the WHO benchmark includes: 1) Naturopathic history, philosophies, principles, and theories. 2) Naturopathic medical knowledge, including basic sciences, clinical sciences, laboratory and diagnostic testing, naturopathic assessment, and naturopathic diagnosis. 3) Naturopathic modalities, practices, and treatments. 4) Supervised clinical practice. 5) Ethics and business practices. 6) Research.

Dishonest practitioners

In United States v Dr Mazi 3:21-mj-71156 MAG[2021], a California-based naturopathic doctor is the first person in the United States to face charges of offering fake “homeoprophylaxis immunisation” coronavirus vaccines and falsifying COVID-19 vaccination cards saying that the purchasers of the pellets had received doses of the Moderna vaccine and also spreading misinformation concerning the vaccine.

Also, in United States v. Feingold, 416 F. Supp. 627 (EDNY 1976, USA courts affirmed the conviction of an Arizona naturopathic physician for the unlawful distribution of narcotic (opioid) medications, which naturopathic physicians in that State were specifically prohibited from doing.

Another case in point is the United States v Livdahl, 459 F. Supp. 2d 1255, (S.D. Fla. 2005), in which the USA courts affirmed the conviction of another Arizona naturopath selling unapproved botulinum toxin type A, misrepresenting the product as an FDA-approved drug.

Even in jurisdictions where naturopathic practice is permitted, a few practitioners have been found by relevant courts to be placing the public at risk practising outside their scope of practice, by virtue of representing themselves as medical specialists where they did not possess training.

In the Australian case of Malaguti v. Orchard [2020] QDC 242, a regulatory appeal prohibiting a naturopath identifying as a medical oncologist without specialist qualifications was upheld.

In the USA case Bailey v Arkansas No. CR 97-1442[1964], an insanity acquittee with conditional release based on taking prescribed medications had relapsed, resulting in legal action after ceasing such medication based on advice from a naturopathic physician, with the courts highlighting the act as professional misconduct, though no action was taken as the practitioner was not within the jurisdiction of the case.

Courts have also dealt with criminal offences by naturopaths. An Australian naturopath (Wilson case) was found guilty of multiple counts of sexual assault and rape on patients. Wilson will spend up to 16 years in jail for sexually assaulting 13 patients over almost two decades.

Medical doctors & naturopathy

The Health Care Complaints Commission v Bao-Queen Nguyen Phuoc [2015] NSWCATOD 81, provides an illustrative example of the courts having to take specific action prohibiting an individual practising as a naturopath, after they had been de-registered as a conventional medical practitioner for misconduct and had attempted to resume medical practice under the guise of providing naturopathic services.

In a Slovenia case, Pravnik: Revija za Pravno Teorijo in Prakso, 2018. 135(11-12): p. 823-858, the courts recognised the development of naturopathic practice standards as reducing the impact of inappropriate practice in that country.

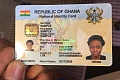

In Ghana, naturopathic practice is increasing even more rapidly than legislative and regulatory tools.

Vivanco Martínez (2009) asserts that in Chile, for example, it has been held by the courts that naturopathic treatment is a valid option for those rejecting other treatments (e.g. cancer treatments), as well as complement those treatments, but that such treatments must abide by similar codes of conduct as conventional medical practice.

Just as appropriate regulations are necessary to minimise the risks of naturopathic practice, inappropriate regulations may increase risks of naturopathic practices.

It is my hope that the Traditional Medicine Practice Council would develop appropriate regulatory arrangements for naturopathic and other alternative medicine practice standards.

This is likely to improve safety and reduce the number of cases involving naturopaths and other alternative medicine practitioners in court systems to avert liabilities.

The writer is an honorary Professor/Final semester LLB student. E-mail: [email protected]