How Coronavirus (COVID-19) has made Ghana’s invisible silent killer of air pollution visible

In the battle to slow the spread of COVID-19, countries around the world are restricting social gatherings, encouraging working from home, closing schools and restricting public events. As a result, this brutal pandemic has inadvertently made the invisible and silent killer of air pollution now visible.

After just a few weeks of these short-term lockdown measures restricting people and vehicular movement, there has been an observable and drastic reduction in traffic and air pollution in major urban cities within both the northern and southern hemispheres.

Advertisement

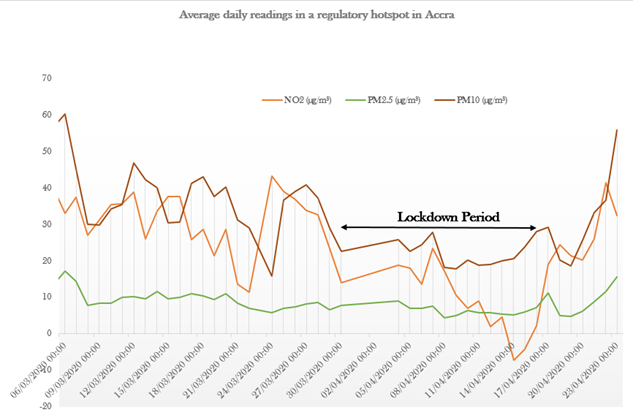

For instance, in Ghana, where I am leading an ongoing research sandpit that uses real-time low-cost air-monitoring sensors, air pollution levels fell by unprecedented levels in a monitoring hotspot in Accra during coronavirus lockdown.

But, there is a steady rise to pre-pandemic higher levels ever since the lockdown restrictions was lifted (see figure below).

Funded by The Institute for Global Innovation (IGI) and Institute of Advanced studies, and partnering with University of Ghana, Department of Geography and Resource Development, including other government bodies, such as the Environmental Protection Agency and Ghana Health Service, the study aims to explore air pollution health impacts and monitor in real-time the levels of key toxic pollutants, such as nitrogen dioxide (NO2), ozone (O3) and particulate matter (PM2.5 and PM10) in major Ghana’s cities.

Air pollution is responsible for over 28,000 premature deaths every year in Ghana, with regulatory measures to robustly tackle air pollution still lacking – just as they are in other major world economies, including the UK, Europe and US.

Many of the pre-existing health conditions – such as cardiovascular disease and asthma – that dramatically elevate the risk of complications and death from COVID-19 are well known to be caused by long-term exposure to high concentrations of toxic air pollutants.

Thus, people with pre-existing conditions living or working in more polluted cities are particularly at risk of respiratory problems or being hospitalised by COVID-19. New studies, including one from Harvard University, also link air pollution to significantly higher rates of death in people with COVID-19.

This correlation between the COVID-19 mortality and morbidity rate and poor air quality shows the urgency for policymakers to start discussing ‘cleaner air for all’ and reboot efforts once the pandemic is over.

Like many government and World Health Organisation public messages and actions for COVID-19 prevention and control, such as physical distancing and washing your hands for 20 seconds, couldn’t there be similar messages and actions for how to breathe and maintain cleaner air? After all, clean air is also key to ‘flattening the curve’ of thousands of premature deaths each year. And while avoiding a post-pandemic recession is important, this is not the time to start relaxing environmental pollution rules on struggling businesses and economies.

A jump-started economy that continues to choke so many people to death from air pollution is suboptimal in ‘flattening mortality curve’ - and not healthy for anyone.

Bringing it all together

With ten years left for the international community to achieve the Global Goals (SDGs), we cannot afford to return to a pre-pandemic ‘business as usual’ scenario. And policymakers should be looking to strengthen urban air quality and environmental emissions regulations to maintain the lower pollution levels of recent weeks.

Crucially, authorities with power also need to take into account issues of social vulnerability and the disparity in the vulnerable, disadvantaged or poorer people’s access to power, knowledge and resources.

Only by policymakers risking their political values and philosophy, to deal with ‘the politics of disadvantage’ and make better socio-environmental quality a key building block of local community planning, can we hope to create more equitable and resilient societies that will be better future proofed against any resurgence of the virus or another global shock.

By: Dr. Nana Osei Bonsu - Research Fellow in Sustainability at the Centre for Responsible Business, Birmingham Business School, University of Birmingham.

In collaboration with: Professor Martin Oteng-Ababio - Head, Department of Geography and Resource Development, University of Ghana; Dr. Mary Eyram Ashinyo - Public Health Physician Specialist & Deputy Director Quality Assurance - Ghana Health Service; Mr. Emmanuel Appoh - Head of Environmental Quality, Environmental Protection Agency; Mr. Stephen Nana Essuman - Programmer Land Use & Spatial Planning Authority and Dr. Louise Carol Serwaa Donkor - Policy and Communications Analyst at the Presidency.

If you’d like to know more about this research, please email: [email protected].