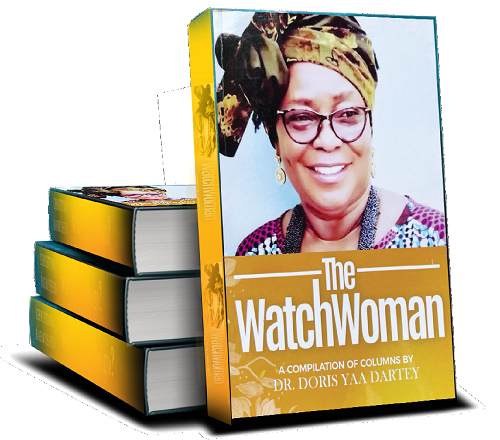

The WatchWoman

I vividly recollect suggesting to Dr Doris Yaa Dartey to have her series in the Weekly Spectator column published into a book.

I was convinced her thoughts and analyses on topical issues deserved to be preserved for the future. Perhaps, I was not alone in the book publication idea.

Advertisement

She bought into my suggestion, but the book idea was not attractive then, however, good and important. My sense of urgency was not hers. Dr Dartey apparently was somebody on a race against time. She was on a one-woman mission to jolt political leadership, provoke the ruling elite into action, and stir up dormant Ghana from lay-back slumber.

Several political and social challenges were consuming up Ghana. They needed to be undressed and addressed. Mother Ghana was at a point of decline and decay. Dr Dartey regarded ugly, incessant public discourse more urgent than a book!

With hindsight, she was right! A compilation of her articles into a book would have prematurely ended a passionate desire to continuously stir up social and political issues. A book would have sealed up her mouth from uninterrupted discussion and analysis of current issues.

Her passion would not be corked up. This posthumous publication has served well Dr Dartey’s desire: to pour herself out on unfolding issues, at a time the country needed to hear her deafening, if lonely shrill voice.

Dr Dartey’s column was about everyday life, the challenges of the disadvantaged, the down-trodden, the “koko” seller, the goat thief and, even more, the apparent insensitivity of well-placed persons in Ghana’s contemporary history.

The over 400-page WatchWoman is a call for serious public discourse on patriotism and national discipline. The book captures highlights of her deep insights into current political issues, economic matters, environmental dangers and many social challenges.

Its 27 chapters raise a lot of red flags for policy makers. They demarcate clear, thematic areas for introspection. The author categorises a two-part list of particular and general “to-do-things”, targeted at both the political elite and the public at large.

Her writings leave no doubt as to the thrust of her sympathies. To policy makers and opinion leaders, it was a call to action for improvement on poor governance, sanitation, health, corruption, personal integrity, politics, fraud, youth hawking and many, otherwise, imponderables.

To the ordinary Ghanaian, it was an urgent invitation for self-reflection on literacy, stigmatisation, personal integrity, fraudulent academic titles, fake news, financial illiteracy, outmoded traditions, parenting, disability and a few more.

Dr Dartey did not set out to write about individuals. Her writings were about Ghana. She accordingly was able to speak her mind and spit out whatever she considered to be the truth. Unafraid to offend, no topic was a sacred cow: the mighty, the untouchable, the larger than God pastor, a First or Second Lady, the President, the IGP, a state institution, etc.

In all of this, her writings reflected the finesse of a colourful literary writer and a scholar, except when the sharp tongue of an aggrieved person had to drive home some specific urgency.

She was clear in her mind that the ruling elite, the governing class and politicians, in general, always put themselves first; and are not willing to share power.

That they mercilessly suffer from policy incompetence.

The author also worried about our typical “Ghanaian nature” – our education that leaves us without values and moral skills for life. The sound bites: “abnormal becoming normal” and “habitats feed habits” are loud expressions of her justifiable frustration.

She loved to spice her articles with evidence-based data: She conducted a quick 2-hour focus-group discussion to sample the views of children on plastics. On other occasions, she relied on published works (the SEND GHANA study) to advance her analysis and commentary on free school uniform.

Dr Dartey was an intimate person and would occasionally bring intimacy into her writings. Indeed, some of her articles are actual and bold revelations, be it her extended family members, close friends or a cousin. She took great risk, too!

Her article on poor teaching and learning at her grand-daughter’s school eventually caused the poor student’s exit. She characteristically concluded her articles with food-for-thought, or what she termed “enduring questions.” It was as if to ask: ‘Isn’t it time for Ghanaians to have an honest discussion about social inequalities and the poorest of the poor?’

Dr Dartey was careful with words, and precise in language. She never said a government is/was doing nothing. However, she detested gesture politics that continually buries away Ghana’s problems. She was understandably angry that polarised, partisan politics brushes poor performance. Dr Dartey was deeply passionate about the missing humanness of officialdom, but yet essential to drive any national transformation agenda.

She also worried that Ghanaians do not openly display the real human impulse. She confessed her lowest mood, when she wrote that “at a point, where leaving my house to go to the heart of Accra or towns or villages depresses me beyond measure”.

Long before the “fix” word gained a central place in Ghana’s political lexicon, (including former President John Mahama’s use of it in his February 2015 ‘State of the Nation’ address), Dr Dartey had used the expression several times over. She directly addressed sitting Presidents with five “Fix the Country” messages: “…Fix our water sanitation and hygiene.” “…Ghana must fix its healthcare delivery system”; “…fix what is wrong with Accra” “…fix the brokenness and hopelessness”; “…fix our problems”; “…we want all of them fixed.”

To her Ghanaian compatriots, she equally directs five similar “Fix Yourself” messages: “…Fix the brokenness and hopelessness”; “…Fix this homeland Ghana”; “…Fix the school”; “…Fix the ramshackle family house”; “…Fix the wrongs”; Dr Dartey rightly deserves the credit of being the originator of the “Fix the country” mantra.

Journalists are not news makers; it is their stories that make news. And so, the author used her articles to irritate, in the good sense of the word. She was not asking for the impossible. Ghana’s problems are not beyond solution.

All she wanted was that many more people should question the actions and inaction of officials that failed to provide solutions. Dr Dartey’s book should make news for a long time to come. The eloquence in her writings, above all, makes the book a vital textbook for a course on “column writing” in our journalism training institutions.