Prof. Nketia shares his love for music

In 2017 with the aim of connecting all ages across the Commonwealth, CommonAge, the Commonwealth association for the ageing, invited young people living in Commonwealth countries to spend time with a monagenarian in their community and write that person's life story. Selected essays were published in a special book in March 2019 to celebrate ageing in the Commonwealth and Her Majesty the Queen of England's 65 years as Head of the Commonwealth.

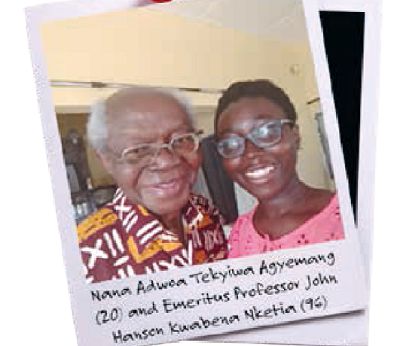

The book's journey through the Commonwealth starts in Ghana with the essay 'Playing to the Tune of Providence', narrated by Emeritus Professor J.H. Nketia to Nana Adwoa Tekyiwa Agyemang.

Life for Professor Nketia began on the 22nd of June, 1921 in Asante Mampong, a town to the north-east of Kumasi, nearly 273 kilometres away from Accra. Born Kwabena Nketia, the only child of illiterate parents, he spent his early years, up until age 7, playing with other children in his community, learning children’s songs and dancing. His formal education began when his mother, a farmer, insisted that he should go to school. The nearest school being in Effiduase, Kwabena Nketia walked 25 km daily to attend his lessons. After the end of his first year, he skipped a grade, having been promoted from Standard One to Standard Three. He marvels how that could have happened, being the first of his family to attend school. Then again, things like these, he says, are commonplace in his life.

Advertisement

When he reached Standard 5, he wrote the standard exam for entrance into the Akropong Teacher Training College. His desire to attend the College was born one Sunday evening when he saw members of the college perform. Dressed in white slacks and blue jackets, the students sang Ephraim Amu’s “Bonwere Kentewene” (translation: Bonwere Kente-weaving). Nketia was entranced by the lyrics of the song, the main chorus of which was onomatopoeic, mimicking the sounds made when working a loom to create Kente. He decided then that he would attend this school. He found out that to attend the College, a Presbyterian mission institution, he would have to be baptised and adopt an anglicised name. The name he chose, Joseph Hanson, belonged to a bosom lifelong friend who later became Police Chief of Ghana. He spent four years at the training college, followed by a year of theological training as a catechist at the same.

Turning point

His time spent at Akropong was a crucial point in his life. It was there he learned to play the harmonium and received a formal education in the Twi language. Although he had gone to Akropong primarily to study under Amu, he was mentored by Rev. Danso, a pupil of Amu, instead. Amu by then had been dismissed by the college’s authorities for dressing in his traditional attire of cloth. However, in a brief encounter Amu instructed Joseph Nketia to be original in his music, not merely becoming a copy of Amu’s style. He advised Nketia to explore music from the older generation, much like how he, Amu, began his music career. This, Nketia says, changed his life. On a visit to his hometown, he sought out his grandmother, the leader of a performing troupe, and studied the traditional schools of music. He collected about 60 songs from her, recording these in a manuscript. When he was satisfied with what he had learned, he visited another town and recorded there, again and again.

Next, he was appointed as a teaching assistant within the college, working directly as the assistant to Clement Anderson Akrofi. Mr Akrofi was an educator, theologian, and linguist, the foremost authority on Twi in his lifetime. It was under Akrofi that Joseph Nketia began exploring and researching Ghanaian culture. Then in 1944, a representative from the School of Oriental and African Studies (SOAS) at the University of London (UOL) visited the college. When she chanced upon Nketia’s manuscript, she offered him a scholarship to study there for the next two years, which was then extended by three years.

New opportunities

On the subject of his stay in London, he says with a smile, “Well I was young and it was interesting. It was during the wartime, but it was exciting.” The bombing on London meant that travel by air was next to impossible, so he went to England by boat. While explosives falling on London meant living in constant fear for many, Nketia speaks calmly about them, saying, “Well sometimes you would hear the warning siren and hide, sometimes it would just fall. Then it was over and you knew that you were safe.”

It was during this time that former Prime Minister Professor Kofi Abrefa Busia, then a member of staff at the University College of the Gold Coast (now the University of Ghana), invited him to join the university’s Department of Sociology as a research fellow. Recognising the importance of Nketia’s research to the country, the position was designed to allow Nketia to further his studies in Ghanaian music and dance. With an assistant and driver, he would travel about the country recording and transcribing performances, songs, and interviews. This invaluable archive can be found in the University of Ghana’s Institute of African Studies. Nketia went on to compose music of his own, with over 40 compositions under his belt.

Love of Music

When asked why he chose music, Professor Nketia laughingly says, “I like it!” He speaks dearly of a love for music stemming from his childhood. Encouraged by a supportive family, he attended the performances of playing troupes in the countryside. These troupes would come from Kumasi to Mampong, and then to Effiduase. Kwabena Nketia would follow the troupes, watching, listening, experiencing.

He insists that the most important thing for him is that everything in his life is a gift of Providence, the hand of God. The only child of illiterate parents in a colonial village at a time when Africa was strictly the Dark Continent, the odds were severely stacked against him. As a child in Mampong, he could not have imagined the path his life would take, let alone plan it. Yet as opportunities presented themselves to him, he thrust himself into them, taking full advantage of each situation, embracing and learning from it.

Learning from our elders

“That kind of mind prepares you to be a researcher,” he says. As a child, he would go to the farm with his mother, and as children are wont to do, copy her by planting yams alongside her. However, at harvest time they would turn out smaller than hers. Then she would ask him questions that made him reflect on and compare the processes the two of them had used in planting and caring for the plants. This was his mother’s way of teaching him, of letting him learn from experiences, a model he kept up with his whole life. He says, "It is the traditional way, we learn from our elders.”

Impressed by Nketia’s knowledge, love for music, and all things related to the African continent, many in positions of power have held him in high esteem. When I left the Professor’s house, he was seated, thinking of what to say at the ceremony at Flagstaff House being held in his honour by the President of the Republic of Ghana, His Excellency Nana Akufo-Addo.The president’s father, former President Edward Akufo-Addo, invited Professor Nketia several times to come over to his home and talk with his children, including a young Nana Akufo-Addo, and teach them how to play the piano.

His association with President Nkrumah began when the leader conceived the Institute of African Studies, inviting Nketia to join the faculty of the new department. After three years working under Professor Thomas Hodgkin, he became its director, serving from 1965 till 1979. His association with Dr. Nkrumah continued, in large and smaller ways. When walking on the street and going about his business, Prof Nketia could expect a wave or some other sign of acknowledgment from the head of state should their paths cross. It was Professor Nketia who was invited to organise and perform at Ghana’s first Republic Day celebrations and concert, because, as he put it, “Nkrumah saw something in me.”

“In fact, I have never had a problem with any of the political parties in power,” he says. This is not a simple feat, rather miraculous in nature, considering Ghana’s political history. In the years after Dr. Nkrumah’s deposition, Professor Nketia wrote a song, the first line of which is “Osagyefo ma wɔn akye oh” (loosely translated, Osagyefo [Nkrumah] greets you good morning) which was broadcasted by public service radio every morning. When General Afrifa heard the song, which praised the leader he had helped depose, playing at a state event, he asked the young woman sitting near him (she was the Comptroller of Programmes at the Ghana Broadcasting Company) who the author was. “My husband,” she replied. At that, he ‘shut up’ to borrow the Professor’s words.

Like Nkrumah, His Majesty the Asantehene Osei Tutu Agyeman Prempeh II, king of the Empire of Ashanti (1931 - 1970), encouraged Professor Nketia’s activities, attending concerts he gave in London, constantly inviting him to the Manhyia Palace in Kumasi. He regularly attended his performances, acting as a self-appointed tutor and mentor to a younger Professor Nketia. Smiling bemusedly, Professor Nketia recounts how he would pop by the palace and the Asantehene would be informed of his presence, immediately halting other activities to come visit with Nketia and talk with him.