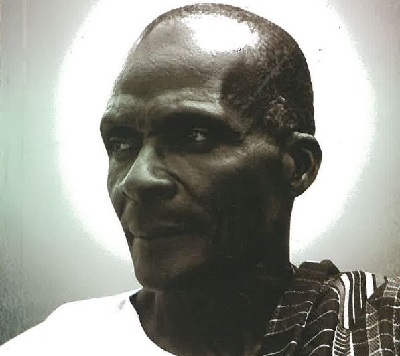

Quality education depends on skills, applications in loving memory of Ephraim Amu

Of the African colonies (after the Scramble for Africa, from 1881 to 1914) the Gold Coast evolved foremost as the citadel of education. It’s no accident that the Gold Coast was to become the first to achieve freedom from colonial rule (1957), setting the example for the rest of Africa south of the Sahara, including notably the two behemoths: Nigeria (1960) and apartheid South Africa (1994).

Advertisement

So how come today, 60 solid years after independence come sixth March 2017 – a sizeable portion of Ghana’s population borders on illiteracy, with schools in some districts scoring majestic zeroes in tests of basic literacy and numeracy? And why do the various governments, one after the other, continue to build majestic offices where some tend to bask in air conditioners listening to political insults, watching movies about superstitions and pushing paper? Won’t it be wiser to spend those resources building factories to produce for the nation’s needs? Wasn’t independence about avoiding dependence on others? Such concerns ought to keep rocking the nation’s conscience until they are resolved.

Ephraim Amu’s accomplishments were many and varied. In reading about him, and asking questions of Prof. J.H. Kwabena Nketia, who worked with him, what stuck to my mind were the qualities in the metaphors that he taught his pupils to live by; that it is great to learn to play music; it is even greater to compose your own songs; but it is greatest where you make your own instruments to produce and play your own tunes.

Amu knew that the wrong education metastasised into intellectual wastes; it defeated practical initiatives; the collateral damages caused helplessness and poverty. The educated person today has to be able to function in two modes simultaneously. The “intellectual” mode focuses on knowledge and actionable ideas; the second mode follows the first and insists on action, and that is the “hands-on” phase with focus on the world of work and progress. Work then may be defined as a product, a useful service, or a solution to any of the plentiful problems that poor nations suffer.

Needy countries tend to be their own worst enemies; they unwittingly create the false impression to the youth that education is about sitting in comfort zones for years on end reading and answering questions from textbooks. Vicious cycles of poverty can be avoided through the discipline of action: that particular point has to percolate and saturate the curricular objectives of traditional universities where the lecture circuits tend to reign supreme.

The two key verbs, “to learn” and “to produce”, speak volumes. Critical thinking methodologies (captioned as Profile Dimensions in the Ghana Education Service (GES) syllabus) work on the precept that education has to be useful. Instruction has to follow a sequence starting with the lower level profile of knowledge acquisition and understanding, that is “to learn”; and end with the higher level profile of applications, that is “to produce” by applying what was learned to alleviate poverty.

The lack of adequate thought about the key purpose for education in a developing country imposes structured idleness and poverty. The needs of a developing country are so many that to have colonies of bright energetic young people strapped behind desks daily is senseless. Relevance boils down to preparing the youth for useable skills.

Curricular objectives are worthless if they are merely good intentions; they must be transformed into work experiences. Serious objectives are commitments; they determine the future; they mobilize the resources and energy for both the present and the perceived future.

Ephraim Amu was the living example of the applications approach to education, and he took pride in getting useful things done. He lived animated by the tenets of his own teachings; for example, visibly carving out musical instruments from reeds, bamboo, wood, leather, etc. and sounding original notes from them. With that creative mindset, his genius evolved.

Though born an Ewe, he mastered Akan, and composed classics in the acquired language. Similarly in agriculture, Amu moved that active mindset into farming in the school grounds. He searched for improved ways of getting things done, even to the extent of processing the night soil into fertilising manure for better crop yields. It wasn’t as if he simply lectured from an ivory tower, or did the softer things. Both he and his pupils were in the trenches doing the menial stuff and learning from each other. His enthusiasm primed his pupils into action.

Such was Ephraim Amu’s genius, long before “domestication” became the yardstick for sustained independence. He taught his students that situating one’s self properly is an essential tenet of freedom. Critical thinking extends one’s freedom to think progressively, to act on the thinking, and then reflect on the act. For him, one could not possibly develop confidence and enjoy freedom without the ability to produce the bare necessities that raise living standards and promote longevity. (He lived to be 95 years.)

He believed in his soul that Ghana could be a more dignified, prosperous, and happier nation by producing things locally, especially growing her own food, investing skills in the youth, and living sober lives. And he used music as the springboard to espouse the wisdom in cutting one’s cloth to size.

Imagine that in lieu of the political tirades, insults and news of officials’ corruption that often flood the airwaves, the nation is allowed the reflective space to listen to Amu’s ace composition, “Yɛn Ara Asaase Ni.” The lyrics embody the living soul of the nation, the direction it should steer, and the responsibility of each citizen to add value to the nation in diverse ways.

[Email: [email protected]]